Chasing the ACE

A bad upbringing is the root of all evil - but it's not an inevitability

Hi! 👋 This is Some Other Dad—the weekly newsletter about the day-to-day joys and challenges we face as parents. Click the button below to subscribe, so you never miss an issue!

I’m a big professional wrestling fan. Since the age of six, half of our home’s VHS collection was WWF (now WWE) pay-per-view shows—some bought, some recorded by my mum at 1am, as they went out live.

A huge feature of those events, as well as the hours of weekly programming I watched at that tender age, was the man behind it all: Vince McMahon.

So when I heard that Netflix were making Mr. McMahon—a documentary about his life and career—I was naturally intrigued.

Being into wrestling for so long, I’m well aware of what a problematic character Vince is. All you have to do is look at some of the risqué storylines and the objectification of women and ethnic minorities during the peak of WWE’s popularity in the late ’90s and early ’00s, and you could deduce that the creative mind behind it all probably belonged to a rather strange bloke.

Confirming these suspicions in no uncertain terms were two pieces of news within the last few years about McMahon: firstly, he was forced to resign after he was found to have used company money to pay hush money to a number of people to conceal multiple affairs; then after he wormed his way back into the company, he was made to resign again after a lawsuit from a former employee alleging sexual abuse, sex trafficking and more.

These two stories were the precursor for the documentary series—which goes into more detail about all manner of other allegations and accounts of his behaviour over the years. But the first episode focused on Vince’s upbringing, which was something I knew little about.

Vince came to own WWE when he bought it off his father, Vince McMahon Sr., in 1982. But he didn’t actually know his father until he was 12 years old. Just after Vince Jr. was born, Vince Sr. left his wife and took his older son with him. Vince Jr. then spent the formative years of his life bouncing around trailer parks, living with his mother and his stepfather. During this time, Vince Jr. says he was beaten “every day” by his stepfather. He also alleges sexual abuse by both his stepbrother and his mother.

Even after he met his father and worked with him, taking the family business to levels of success Vince Sr. could only imagine, his father only ever told him he loved him once: on his death bed.

Was I shocked by these accounts? Yes. But knowing everything I already did about the man Vince had become, was I surprised? Not at all.

ACEs and their impact in later life

It’s all too common that see a news report about someone that’s done something depraved or awful, then years later you get the documentary that, within the first ten minutes, utters words along the lines of “they had a very difficult childhood”.

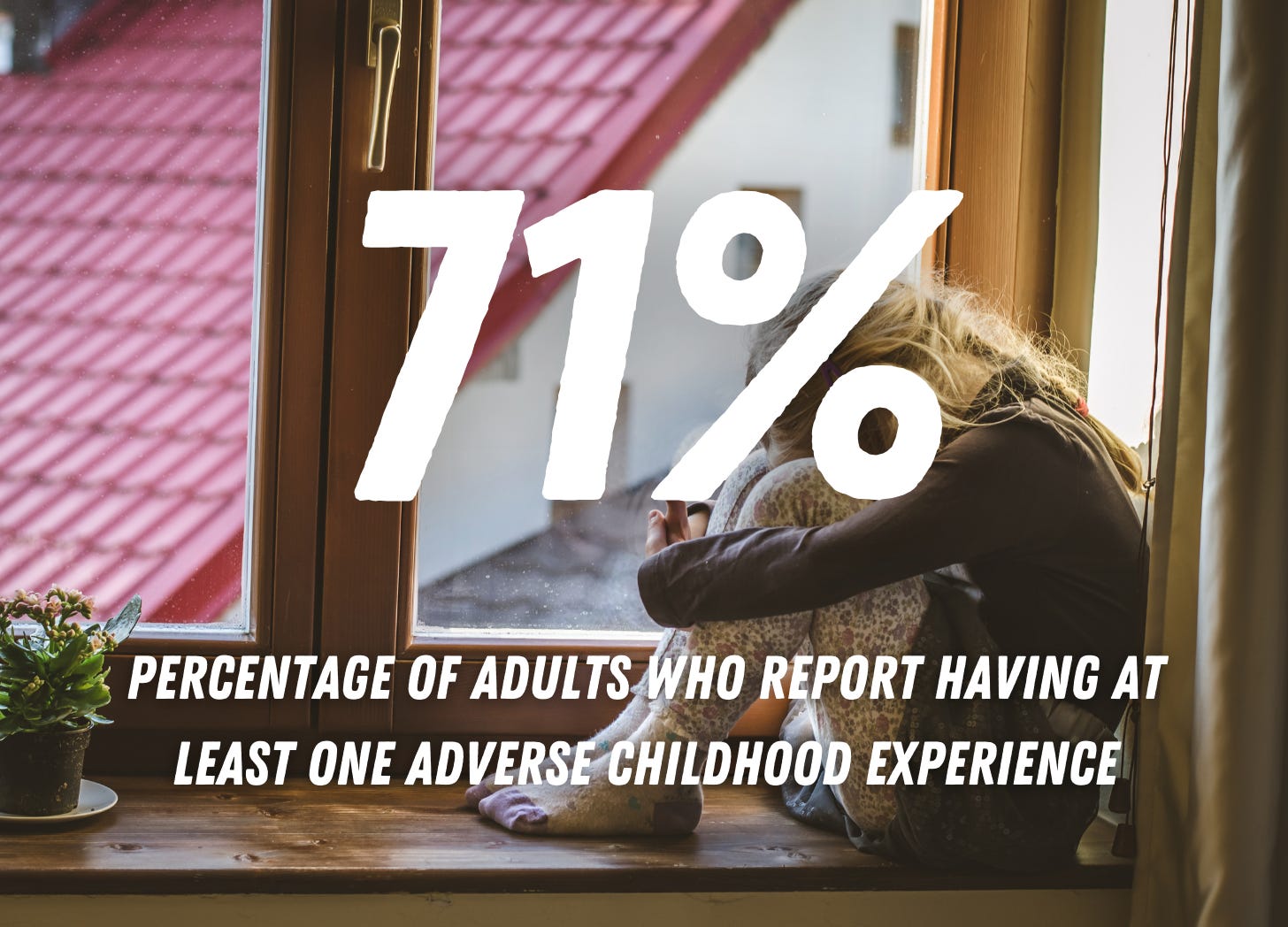

71% of adults report having experiences at least one adverse childhood experience—or ACE. Studies unequivocally show that the presence ACEs make the likelihood of that person engaging in criminal behaviour in later life significantly higher. One such study from the University of Edinburgh took a sample of over 4,300 people and found that 25% had at least one criminal conviction by the age of 35. When looking further into those with criminal records, researchers found that factors such as drug use during adolescence and being a repeated victim of crime could be linked with continuing to offend into early middle age1. They also found that the presence of ACEs–such as “bereavement, relationship breakdown, and having a serious accident or illness”–also contributed to a person’s likelihood to become involved in crime.

Another report in the USA highlighted that childhood abuse and neglect can foster anti-social behaviours in adolescence, which often carry on into adulthood. These behaviours include increased aggression, risky decision-making, and the development of unhealthy relationships: all of which can contribute to a propensity to become involved with criminal activity.

Interesting as these statistics and studies are however, they really just confirm what we anecdotally already know. You’ve probably got someone from your own life in your mind’s eye when you’re reading this. I know I have. I still remember seeing a notorious member of my school year group decades later, dressed up in a suit, before realising that they were walking towards the courthouse. I read about the case in the local news days later.

So what does this have to do with parenting?

Granted, some ACEs can come from things well beyond anyone’s control. But further research from the CDC suggests that a majority of ACEs experienced occur in the household, indicating parental or caregiver involvement, either directly or indirectly.

ACEs are complex. When we talk about them, we tend to think about the worst possible kinds, such as physical and sexual abuse. But recently the definition has broadened from what was previously indicated by the earliest studies.

I’m willing to wager that the vast majority of us can recall some incident from our childhood that still shapes how we perceive the world today. Not to sound too dramatic, but that’s probably an ACE.

“But other people have gone through way worse stuff in their lives,” is a typical response to that, because it’s exactly what I said to my therapist once when discussing this very topic. The answer to that is the old maxim that we’re all different. And part of that is we all react in a unique way to each and every situation. Something that happened in my childhood that has stayed with me for years might have been forgotten about years ago by you, and vice versa. You only have to look at the trajectory of Prince William and Prince Harry’s lives to see that in action. They went through the exact same trauma—one decided to stay in the institution that indirectly led to it, and the other left.

How to live—and parent—with an ACE

I’m not trying to scare-monger you all into thinking that we’re just one step away from fucking our kids up for good. The point that I’m getting to—and the main thing that jumped out of me as I watched the early and later episodes of Mr. McMahon—is that for all the statistics about criminal behaviour in later life and so on, the biggest fulcrum in the life of someone with an ACE is when they become a parent.

We all know kids are like sponges. They see, hear and take in everything around them. It’s alarming just how many times my daughter can parrot back to me something I said six months ago, word for word. So naturally, any ACE we have shapes our worldview and will likely affect our parenting playbook—as I’ve written about before.

The first step of anything to do with mental health is acknowledging that it’s there, and that it exists. You can’t fight an enemy you can’t see. “The best thing we can do for the children we care for is to manage our own stuff,” says Donna Jackson Nakazawa. “Adults who’ve resolved their own trauma help kids feel safe.”

I’ve also written before about how kids know exactly how to push our buttons; and this can be linked to ACEs that we experienced. Parents who have experienced ACEs generally report feeling more stressed and irritable as they become parents.

Of all the times where I notice my past experiences shaping how I parent my own kids is when I’m dysregulated; something has triggered me or thrown me for a loop, and then I’m parenting by numbers, which is often when we find ourselves talking like our own parents.

Anything that I can do to remain as present as possible, even in stressful situations, allows me to react to the latest parenting chaos in a measured way; the way that I’d want to react if I could see the situation coming a hundred miles away.

I don’t share this as advice for preventing ACEs in our own kids. Statistically, it’s more likely than not that it will happen anyway. But by being able to better regulate myself puts me in a better mental position to be able to listen and respond to what my children are feeling. I hope this in turn will foster an environment where they’re completely comfortable expressing their concerns with us as their parents, something which I never had.

I always think of it as like putting a pair of jeans in the dryer by mistake. If you have them in there for the full three hours, those creases are baked in and they’re shrunk for good. But the earlier you get them out of there and address it, the better. Alright, there might still be a few minor creases, but they can be ironed out.

Breaking the cycle is hard. And no, I’m not still talking about dryers. Generational trauma takes years of unpicking. Sometimes I resign myself to it being my life’s work. But if it means my daughters don’t have to go through nearly as much as the same shit, then it’s been worth it.

On-screen Generational Trauma

As much as the majority of the subject matter of Mr. McMahon was hard to watch for the majority of viewers2, there was a bright spark at the end of the piece that centred around Vince’s son, Shane. Just like his dad before him, he became infatuated with the wrestling business by watching his own father running the show. All he wanted to do was impress his dad and follow in his footsteps.

He put himself through his fair share of insane on-screen stunts. When I watched when I was young, I couldn’t believe that a non-wrestler was jumping through glass, falling off platforms 30 feet in the air through tables, when someone trained in the wrestling business would rightly say “fuck that”.

But it all makes so much more sense now. All that death-defying stuff was a response to the lack of attention and affection from his father—the same ACE that Vince himself went through twice; first in the twelve years of his life after Vince Sr. abandoned him, and in the years afterwards where he tried and tried to make his father proud, with little affection shown in return.

I see Shane now as a cycle-breaker. Rather than continue on the endless pursuit of his father’s approval, he left the company in 2009, only returning on his own terms, when Vince called him to do a match at Wrestlemania 32 in 2016.

In the backstage clips before Shane walks out in front of the crowd, he talks to his three sons and invites them to come out onto the stage with him. They look awe-struck, and after the match the affection that he shows each of them is clearly apparent, and in stark contrast to the father-son dynamics shown throughout the rest of the documentary.

Then, battered and bruised, Shane turns to his dad. They share a hug, and although the things revealed about Vince in the rest of the documentary are downright monstrous, I couldn’t help but be moved by the barest hint of tears as he shared that hug with his son. Decades of generational trauma welled in his eyes; his father’s, his own and his son’s.

But my emotions were not for Vince—but for Shane, the cycle breaker. I always rooted for him as a kid. Now I know why.

Thanks for reading!

I never thought I’d be writing about wrestling and parenting at the same time, but here we are! It just struck me as I was hearing about Vince McMahon’s childhood how often we hear about troubled upbringings when we examine people who’ve done terrible things, and so it just made sense to write about. I know I’ve spoken before about generational trauma and breaking the cycle, but I think it’s genuinely one of our greatest challenges as parents, so I’ll probably end up talking about it again in the future!

As ever, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this week’s issue!

As a 34-year-old, I’m more than slightly perturbed that they describe 35 as “early middle age”.

I only say this because as someone who’s followed wrestling and wrestling news for decades, most of the stuff in there was stuff I already knew. Objectively though, I’m obviously well aware of how bad it is.

Great article. Thanks for sharing your experience. Perception is our reality. You will stand in your daughter's judgement one day and they will have their say in how they think you did. if you try to teach them about budgeting and thrift, they can say you were too hard on them on their finances a a Kid. It's their call even though you'll do the best you can.

I have a friend who once said to me that she just hopes her kids go to therapy for different reasons than she did, and that stuck with me. No matter how hard I try, I'm going to stuff up! But hopefully I can learn from my parents' mistakes and stuff up in all new ways